What if?

10/11/19 17:00

The story below was originally presented in our Chapter Newsletter in April, 2018. As Verteran's Day is approaching, I thought it appropriate to publish it here on our new website.

—

Photo: Looking east across western Idaho from 11,500 feet. (Clear skies and smooth terrain to the west.)

What if?

By Alan Collins, February 28, 2018

Over the past few months I’ve been shopping for a good quality, older, Cessna to compliment my smaller Zenith 601 experimental. I found what I wanted in Coeur d’Alene Idaho, and in late February I flew my first long cross-country trip bringing her home to Blake Field. It was both exciting and a learning experience. However, meeting and talking with the previous owner was just as interesting. Below I’ll share his story, and as you begin to connect the dots I think you’ll find it quite remarkable.

Photo: Richard Le Francis (junior) and Alan Collins.

The museum has thousands of artifacts, primarily from World War II. Unfortunately, the museum lost its lease last year, so exhibits are only available online (pictures and videos) for now. Richard is working with Burt Rutan, also a resident of Coeur d’Alene, and others to secure a new location. Until then, visit the museum’s YouTube channel. Ed.: Update from Richard: "The American Legion Post in Post Falls has acquired most of the Artifacts of our museum and is actively trying to acquire funding for a small museum at their location. Dale [Childers] and I will continue to tell veteran stories on our tube channel at the website."

I took off from Coeur d’Alene (KCOE) at about noon and flew almost due south to avoid weather to the east. (See picture at the top.) As I made my way over a sea of scattered clouds, I recalled the fascinating story Richard told of his father’s experience, Richard Le Francis senior, just prior to the end of WWII.

Photo: Simulated photo of C-54 flown by Cpt. Le Francis, coutesy Dale Childers.

In late July, 1945, Cpt. Le Francis saw something extraordinary, a story best told in his own words. Below are excerpts from a letter or diary of sorts the senior Le Francis wrote to his son and namesake:

"After several shuttles back and forth between islands we arrived at Nichols Field in Manila on the 27th of July. We loaded passengers and cargo and prepared to depart for Guam on the 29th of July. One of my passengers was an Army Brigadier General who was MacArthur's artillery officer.

"Prior to take-off I had been briefed that the Navy had been scheduling target practice for the fleet someplace between the Philippines and the Marianas. We were to stay about 20 miles north of the target area. The take-off had been at night, and we arrived at the target area about 9,000 feet. We observed massive firing by naval ships quite south of us but evidently targeting an object 10 miles to the south of us. I called the general to the cockpit, placed him in the co-pilot’s seat so he could view the naval artillery in action. He enjoyed the action and commented that the target seemed to be firing back. We all thought this was humorous, but it appeared to be that way. Our observation of the action was fleeting and soon we had proceeded beyond the practice area.

Total flight time from Coeur d’Alene ID to Delta CO in my Cessna 182 (excluding an overnight stop in Burley ID) was just over eight hours, slightly longer than it took a C-54 to fly ~1600 miles from Manilla to Guam during that night in July 1945. Cpt. Le Francis continues:

"The next day at Harmon Field in Guam I got a ride to the Navy end and reported to a Navy commander that we observed the action where the object of practice seemed to be a large ship being sunk, and that the General had believed it fired back. The commander told me that he had no knowledge of any practice in that area and that we probably didn’t see any action as described. I let it go at that.

On July 28, 1945, the day before Cpt. Le Francis took off for Guam, a ship left Guam sailing the other direction towards Leyte (another island in the Philippines). The heavy cruiser had just completed an historic mission to deliver parts and enriched uranium for the atomic bomb Little Boy to Tinian island (Northern Marianas).

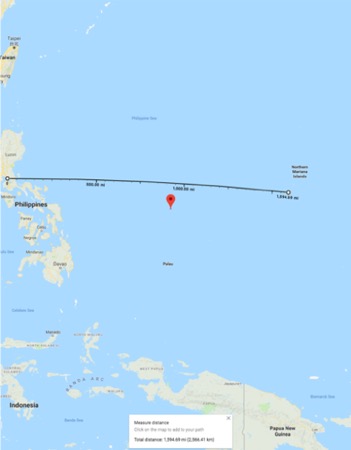

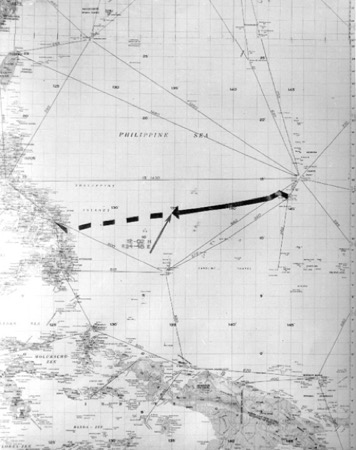

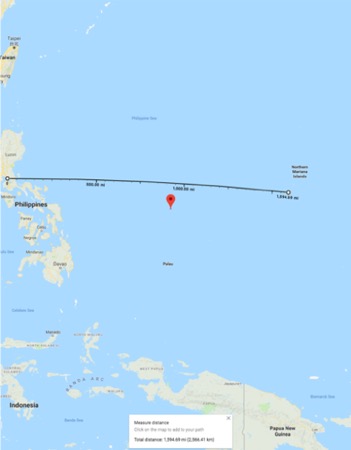

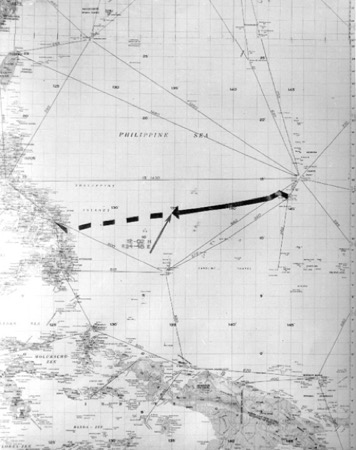

Photo: Left: Distance from Manilla to Guam approx. 1600 miles (Google Maps). The pin indicates the location of the Indianapolis at the time she sank. Right: The Indianapolis's intended route from Guam to the Philippines.

At 12:15 am July 30, 1945, the USS Indianapolis was about half way from Guam to Leyte. At about the same time, the C-54 was half way from Manilla to Guam. The Indianapolis was struck by two Japanese torpedoes. Massive damage caused the ship to list then settle on the bow. Twelve minutes later she rolled completely over, the stern rose into the air, and she sank.

Of nearly 1200 sailors on board, ~300 went down with the ship. The remaining 900 faced exposure, dehydration, saltwater poisoning, and shark attacks for nearly four days. By the time they were rescued, only 317 had survived. The sinking of the Indianapolis led to the greatest single loss of life at sea, from a single ship, in the history of the US Navy [Wikipedia].

Rather than a sea battle, it is likely that what Cpt. Le Francis and the General saw that night were signal flares from the crew of the Indianapolis. Cpt. Le Francis continues:

"Two days later it was announced on the island military radio that the Indianapolis had been sunk at about that area that we saw the practice bombardment. When I notified the Navy again of our observations, they disregarded the information. When I finally arrived at Hamilton Field some time later, I informed our base intelligence officer of the incident and he told me to forget it, that it was a Navy problem. I was not satisfied with the answer, so I called the FBI in San Francisco and they sent an agent out to my barracks. My navigator plotted the exact location of the incident on the map, which I gave the agent. I’ve never heard anything about this since, except what I read in the newspaper.

Photo: USS Indianapolis, July 10, 1945.

What if the commander Cpt. Le Francis reported his observation to had acted on the information? Could hundreds of lives have been saved by rescuing the crew of the Indianapolis sooner? It is impossible to know. There were many areas of communication breakdown, and many factors that contributed to the fate of the Indianapolis.

Back in the more recent past, I arrived at Blake Field in my little Cessna on February 21st without incident. It was a memorable trip, and I got to hear a memorable story of historical significance.

Back in the more recent past, I arrived at Blake Field in my little Cessna on February 21st without incident. It was a memorable trip, and I got to hear a memorable story of historical significance.

—

Ed. In October 2019, Richard Le Francis sent me this update: "About the same time you took over N300DF, a guy my age discovered after his father’s passing, a diary his father kept during the war. He had been on the LST 779(?) when the INDY passed. Both were headed to the Philippines. I am very interested to know if Paul Allen’s research vessel, which discovered the Indy at 15000 ft, triangulated the info from the 779 logs from the sighting and used the coordinates from my father’s navigator, Dave Nadel, which my father provided the FBI shortly after VJ day."

—

Photo: Looking east across western Idaho from 11,500 feet. (Clear skies and smooth terrain to the west.)

What if?

By Alan Collins, February 28, 2018

Over the past few months I’ve been shopping for a good quality, older, Cessna to compliment my smaller Zenith 601 experimental. I found what I wanted in Coeur d’Alene Idaho, and in late February I flew my first long cross-country trip bringing her home to Blake Field. It was both exciting and a learning experience. However, meeting and talking with the previous owner was just as interesting. Below I’ll share his story, and as you begin to connect the dots I think you’ll find it quite remarkable.

Richard Le Francis is Director of the Pappy Boyington Veterans Museum in Coeur d’Alene, dedicated to celebrating and honoring those who served in uniform to preserve the freedoms we enjoy every day. He and his father, Richard senior, owned this beautiful 1966 Skylane since the mid-1980’s. (In fact, he was a little sentimental about letting her go. But I digress.)

Photo: Richard Le Francis (junior) and Alan Collins.

The museum has thousands of artifacts, primarily from World War II. Unfortunately, the museum lost its lease last year, so exhibits are only available online (pictures and videos) for now. Richard is working with Burt Rutan, also a resident of Coeur d’Alene, and others to secure a new location. Until then, visit the museum’s YouTube channel. Ed.: Update from Richard: "The American Legion Post in Post Falls has acquired most of the Artifacts of our museum and is actively trying to acquire funding for a small museum at their location. Dale [Childers] and I will continue to tell veteran stories on our tube channel at the website."

I took off from Coeur d’Alene (KCOE) at about noon and flew almost due south to avoid weather to the east. (See picture at the top.) As I made my way over a sea of scattered clouds, I recalled the fascinating story Richard told of his father’s experience, Richard Le Francis senior, just prior to the end of WWII.

Nearly three-quarters of a century ago, the man who later flew my (relatively) small Cessna 182, Captain Richard Le Francis of the U.S. Army Air Forces, piloted a much larger Douglas C-54 “Skymaster” shuttling cargo and passengers between the islands of the Pacific and the U.S. west coast.

Photo: Simulated photo of C-54 flown by Cpt. Le Francis, coutesy Dale Childers.

In late July, 1945, Cpt. Le Francis saw something extraordinary, a story best told in his own words. Below are excerpts from a letter or diary of sorts the senior Le Francis wrote to his son and namesake:

"After several shuttles back and forth between islands we arrived at Nichols Field in Manila on the 27th of July. We loaded passengers and cargo and prepared to depart for Guam on the 29th of July. One of my passengers was an Army Brigadier General who was MacArthur's artillery officer.

"Prior to take-off I had been briefed that the Navy had been scheduling target practice for the fleet someplace between the Philippines and the Marianas. We were to stay about 20 miles north of the target area. The take-off had been at night, and we arrived at the target area about 9,000 feet. We observed massive firing by naval ships quite south of us but evidently targeting an object 10 miles to the south of us. I called the general to the cockpit, placed him in the co-pilot’s seat so he could view the naval artillery in action. He enjoyed the action and commented that the target seemed to be firing back. We all thought this was humorous, but it appeared to be that way. Our observation of the action was fleeting and soon we had proceeded beyond the practice area.

Total flight time from Coeur d’Alene ID to Delta CO in my Cessna 182 (excluding an overnight stop in Burley ID) was just over eight hours, slightly longer than it took a C-54 to fly ~1600 miles from Manilla to Guam during that night in July 1945. Cpt. Le Francis continues:

"The next day at Harmon Field in Guam I got a ride to the Navy end and reported to a Navy commander that we observed the action where the object of practice seemed to be a large ship being sunk, and that the General had believed it fired back. The commander told me that he had no knowledge of any practice in that area and that we probably didn’t see any action as described. I let it go at that.

On July 28, 1945, the day before Cpt. Le Francis took off for Guam, a ship left Guam sailing the other direction towards Leyte (another island in the Philippines). The heavy cruiser had just completed an historic mission to deliver parts and enriched uranium for the atomic bomb Little Boy to Tinian island (Northern Marianas).

Photo: Left: Distance from Manilla to Guam approx. 1600 miles (Google Maps). The pin indicates the location of the Indianapolis at the time she sank. Right: The Indianapolis's intended route from Guam to the Philippines.

At 12:15 am July 30, 1945, the USS Indianapolis was about half way from Guam to Leyte. At about the same time, the C-54 was half way from Manilla to Guam. The Indianapolis was struck by two Japanese torpedoes. Massive damage caused the ship to list then settle on the bow. Twelve minutes later she rolled completely over, the stern rose into the air, and she sank.

Of nearly 1200 sailors on board, ~300 went down with the ship. The remaining 900 faced exposure, dehydration, saltwater poisoning, and shark attacks for nearly four days. By the time they were rescued, only 317 had survived. The sinking of the Indianapolis led to the greatest single loss of life at sea, from a single ship, in the history of the US Navy [Wikipedia].

Rather than a sea battle, it is likely that what Cpt. Le Francis and the General saw that night were signal flares from the crew of the Indianapolis. Cpt. Le Francis continues:

"Two days later it was announced on the island military radio that the Indianapolis had been sunk at about that area that we saw the practice bombardment. When I notified the Navy again of our observations, they disregarded the information. When I finally arrived at Hamilton Field some time later, I informed our base intelligence officer of the incident and he told me to forget it, that it was a Navy problem. I was not satisfied with the answer, so I called the FBI in San Francisco and they sent an agent out to my barracks. My navigator plotted the exact location of the incident on the map, which I gave the agent. I’ve never heard anything about this since, except what I read in the newspaper.

Photo: USS Indianapolis, July 10, 1945.

What if the commander Cpt. Le Francis reported his observation to had acted on the information? Could hundreds of lives have been saved by rescuing the crew of the Indianapolis sooner? It is impossible to know. There were many areas of communication breakdown, and many factors that contributed to the fate of the Indianapolis.

—

Ed. In October 2019, Richard Le Francis sent me this update: "About the same time you took over N300DF, a guy my age discovered after his father’s passing, a diary his father kept during the war. He had been on the LST 779(?) when the INDY passed. Both were headed to the Philippines. I am very interested to know if Paul Allen’s research vessel, which discovered the Indy at 15000 ft, triangulated the info from the 779 logs from the sighting and used the coordinates from my father’s navigator, Dave Nadel, which my father provided the FBI shortly after VJ day."